< < < J’ai dû être le plus têtu de tous (Ru/Fr) / I must have been the most stubborn of all (Ru/Eng) / Я, верно, был упрямей всех (Рус/Анг.) / (Рус/ Фра.

Ivan Turgenev Demain ! Demain ! (Ru/Fr) / To-Morrow! To-Morrow! (Ru/Eng) / Тургенев Иван Завтра, завтра (Рус/Анг.) / (Рус/ Фра.) > > >

Soon will come the anniversary of the end of the Second World War.

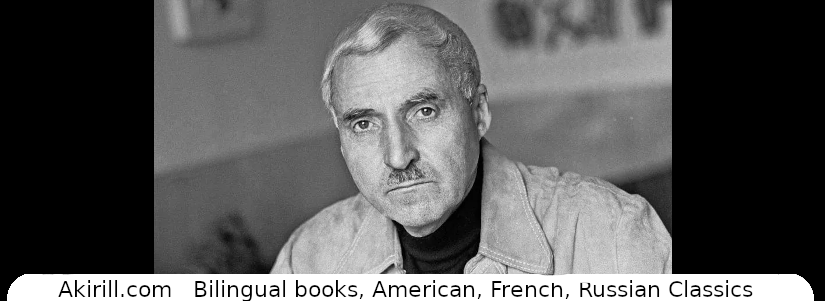

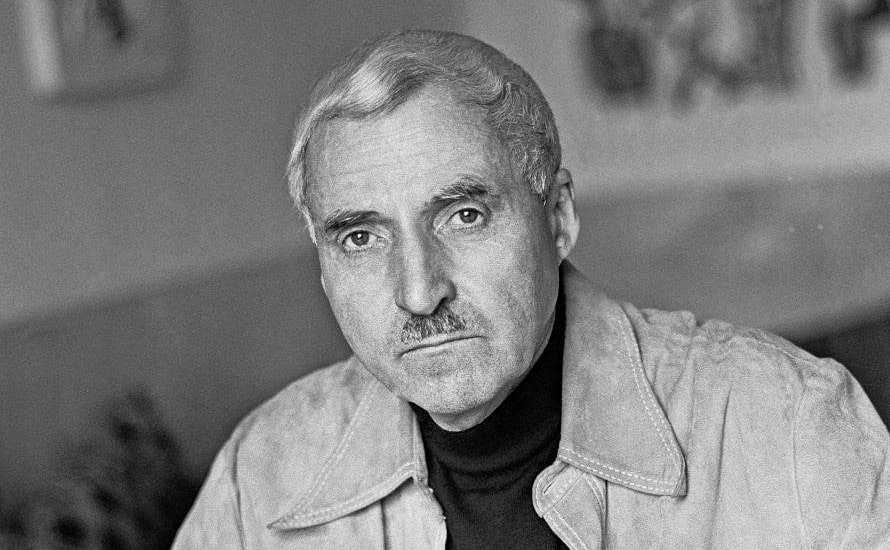

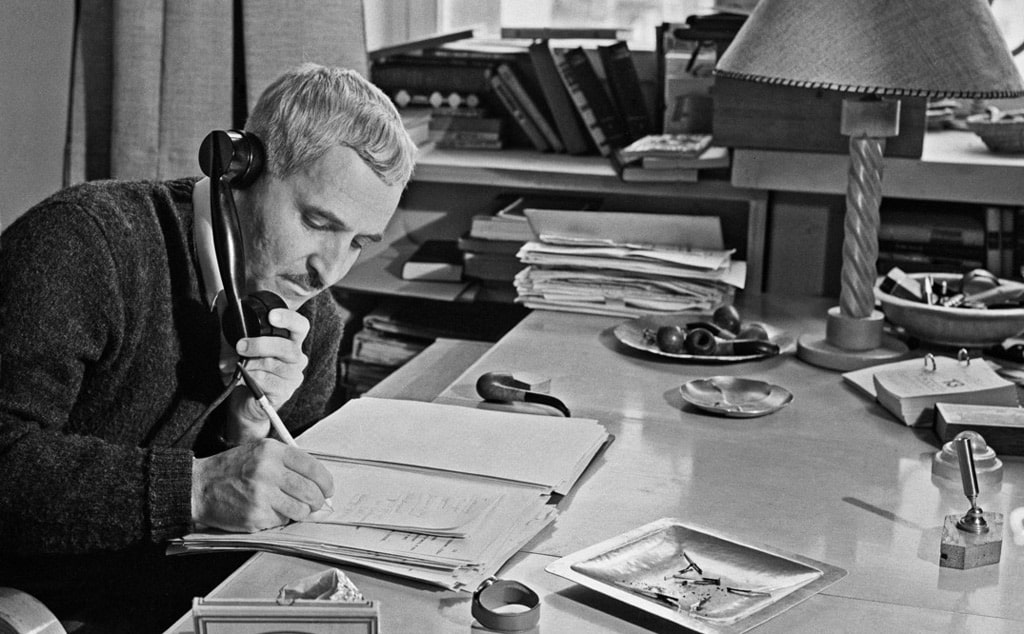

This poem “Open Letter” is based on real events that took place under the eyes of Konstantin Simonov in 1943 in General Gorbatov’s Third Army.

After some time, a deceased senior lieutenant received a letter from his wife containing information, which Simonov reproduced in his poem at the request of his combat comrades.

The poem is imbued with pain for a comrade, fear of the possibility of experiencing the same thing, a reproach to unfaithful women.

The lyrics are under the video

A big thank you to all our veterans.

| Константин Симонов — Открытое письмо | Konstantin Simonov – Open Letter |

| Я вас обязан известить, Что не дошло до адресата Письмо, что в ящик опустить Не постыдились вы когда-то. | I am obliged to inform you, That the letter dropped one day without shame in the mail box did not reach the addressee. |

| Ваш муж не получил письма, Он не был ранен словом пошлым, Не вздрогнул, не сошел с ума, Не проклял все, что было в прошлом. | Your husband did not receive a letter, He was not wounded by a vulgar word , He did not flinch, did not go mad, He did not curse everything that happened in the past. |

| Когда он поднимал бойцов В атаку у руин вокзала, Тупая грубость ваших слов Его, по счастью, не терзала. | When he raised the fighters During the attack in the ruins of the station, The blunt rudeness of your words fortunately, did not torment him. |

| Когда шагал он тяжело, Стянув кровавой тряпкой рану, Письмо от вас еще все шло, Еще, по счастью, было рано. | When he walked heavily, Pulling the wound with a bloody rag, The letter from you was still coming, Fortunately, it was still early. |

| Когда на камни он упал И смерть оборвала дыханье, Он все еще не получал, По счастью, вашего посланья. | When he fell on the stones And death cut off his breath, Fortunately, he did not yet receive, your message. |

| Могу вам сообщить о том, Что, завернувши в плащ-палатки, Мы ночью в сквере городском Его зарыли после схватки. | I can tell you that, wrapped in raincoats, We buried him at night in the city square after the fight. |

| Стоит звезда из жести там И рядом тополь — для приметы… А впрочем, я забыл, что вам, Наверно, безразлично это. | There is a star made of tin there And next to it is a poplar – for a landmark … But, by the way, I forgot that you, Probably, do not care about this. |

| Письмо нам утром принесли… Его, за смертью адресата, Между собой мы вслух прочли — Уж вы простите нам, солдатам. | The letter was brought to us in the morning … After the death of the addressee, We read it aloud between ourselves – Forgive us, soldiers. |

| Быть может, память коротка У вас. По общему желанью, От имени всего полка Я вам напомню содержанье. | Perhaps your memory is short. By common wish, On behalf of the whole regiment, I will remind you of the content. |

| Вы написали, что уж год, Как вы знакомы с новым мужем. А старый, если и придет, Вам будет все равно ненужен. | You wrote that it’s been a year, since you’ve known your new husband. And the old one, if he comes, will still be unnecessary to you. |

| Что вы не знаете беды, Живете хорошо. И кстати, Теперь вам никакой нужды Нет в лейтенантском аттестате. | That you do not know trouble, Live well. And by the way, you don’t need a lieutenant’s certificate anymore. |

| Чтоб писем он от вас не ждал И вас не утруждал бы снова… Вот именно: «не утруждал»… Вы побольней искали слова. | So that he doesn’t expect letters from you And he doesn’t bother you anymore … That’s right: “he didn’t bother” … You were looking for more painful words. |

| И все. И больше ничего. Мы перечли их терпеливо, Все те слова, что для него В разлуки час в душе нашли вы. | And that’s it. And nothing more. We counted them patiently, All those words that for him In the hour of separation you found in your soul. |

| «Не утруждай». «Муж». «Аттестат»… Да где ж вы душу потеряли? Ведь он же был солдат, солдат! Ведь мы за вас с ним умирали. | “Don’t bother.” “Husband”. “Certificate” … But where did you lose your soul? After all, he was a soldier, a soldier! After all, we were fighting with him for you. |

| Я не хочу судьею быть, Не все разлуку побеждают, Не все способны век любить,— К несчастью, в жизни все бывает. | I don’t want to be a judge, Not everyone overcomes separation, Not everyone is able to love forever, – Unfortunately, everything happens in life. |

| Но как могли вы, не пойму, Стать, не страшась, причиной смерти, Так равнодушно вдруг чуму На фронт отправить нам в конверте? | But how could you, I don’t understand, Become, without fear, the cause of death, So indifferently suddenly send us a plague to the front in an envelope? |

| Ну хорошо, пусть не любим, Пускай он больше вам ненужен, Пусть жить вы будете с другим, Бог с ним, там с мужем ли, не с мужем. | Well, let’s not love, Let him be no longer needed for you, Let you live with another, God bless him, whether with her husband, not with her husband. |

| Но ведь солдат не виноват В том, что он отпуска не знает, Что третий год себя подряд, Вас защищая, утруждает. | But after all, the soldier is not to blame For the fact that he does not know the holidays, That for the third year in a row, protecting you, bothers. |

| Что ж, написать вы не смогли Пусть горьких слов, но благородных. В своей душе их не нашли — Так заняли бы где угодно. | Well, you could not write Let bitter words, but noble ones. They were not found in your souls – You could have found them anywhere. |

| В отчизне нашей, к счастью, есть Немало женских душ высоких, Они б вам оказали честь — Вам написали б эти строки; | In our homeland, fortunately, there are many high female souls, They would do you honor – they would write these lines to you; |

| Они б за вас слова нашли, Чтоб облегчить тоску чужую. От нас поклон им до земли, Поклон за душу их большую. | They would have found words for you, To alleviate someone else’s sadness. From us bow to them to the ground, Bow down for their great soul. |

| Не вам, а женщинам другим, От нас отторженным войною, О вас мы написать хотим, Пусть знают — вы тому виною, | Not to you, but to other women, torn away from us by the war, We want to write about you, Let them know that you are to blame, |

| Что их мужья на фронте, тут, Подчас в душе борясь с собою, С невольною тревогой ждут Из дома писем перед боем. | That their husbands are at the front, here, Sometimes fighting with themselves in their souls, With involuntary anxiety, they wait for letters from home before the battle. |

| Мы ваше не к добру прочли, Теперь нас втайне горечь мучит: А вдруг не вы одна смогли, Вдруг кто-нибудь еще получит? | We didn’t read yours with pleasure. Now we are secretly tormented by bitterness: What if you weren’t the only one who could, What if someone else gets it? |

| На суд далеких жен своих Мы вас пошлем. Вы клеветали На них. Вы усомниться в них Нам на минуту повод дали. | To the judgment of our distant wives We will send you. You slandered them. You gave us a reason to doubt them for a minute. |

| Пускай поставят вам в вину, Что душу птичью вы скрывали, Что вы за женщину, жену, Себя так долго выдавали. | Let them blame you, That you hid the soul of a bird , What kind of woman, wife, You gave yourself away for so long. |

| А бывший муж ваш — он убит. Все хорошо. Живите с новым. Уж мертвый вас не оскорбит В письме давно ненужным словом. | And your ex-husband is dead. Everything is fine. Live with the new. Already the dead will not offend you In a letter for a long time an useless word. |

| Живите, не боясь вины, Он не напишет, не ответит И, в город возвратись с войны, С другим вас под руку не встретит. | Live without fear of guilt, He will not write, will not answer And, back in the city from war, He won’t meet you arm in arm with another. |

| Лишь за одно еще простить Придется вам его — за то, что, Наверно, с месяц приносить Еще вам будет письма почта. | Only for one more thing to forgive, you will have to forgive him – for the fact that, probably for months, letters will still be brought to you from the post office. |

| Уж ничего не сделать тут — Письмо медлительнее пули. К вам письма в сентябре придут, А он убит еще в июле. | There’s nothing to be done here – A letter is slower than a bullet. Letters will reach you in September, and he was killed in July. |

| О вас там каждая строка, Вам это, верно, неприятно — Так я от имени полка Беру его слова обратно. | Every line talks about you, it’s probably unpleasant for you – So on behalf of the regiment I withdraw his remarks. |

| Примите же в конце от нас Презренье наше на прощанье. Не уважающие вас Покойного однополчане. | Accept in the end from us, our contempt at parting. Fellow soldiers who do not respect you. |

| По поручению офицеров полка К. Симонов ___________________________ [Женщине из города Вичуга] | On behalf of the officers of the regiment K. Simonov _____________________ [To a woman from the city of Vichuga] |

< < < J’ai dû être le plus têtu de tous (Ru/Fr) / I must have been the most stubborn of all (Ru/Eng) / Я, верно, был упрямей всех (Рус/Анг.) / (Рус/ Фра.

Ivan Turgenev Demain ! Demain ! (Ru/Fr) / To-Morrow! To-Morrow! (Ru/Eng) / Тургенев Иван Завтра, завтра (Рус/Анг.) / (Рус/ Фра.) > > >

We put a lot of effort into the quality of the articles and translations, support us with a like and a subscription or sponsor us if you like them. We are also on Facebook and Twitter

- Poèmes et peinture, semaine du 25 janvier 2026

- Poems and painting, Week of January 25, 2026

- Poèmes et peinture, semaine du 18 janvier 2026

- Poems and painting, Week of January 18, 2026

- Poèmes et peinture, semaine du 11 janvier 2026

- Poems and painting, Week of January 11, 2026

© 2022 Akirill.com – All Rights Reserved