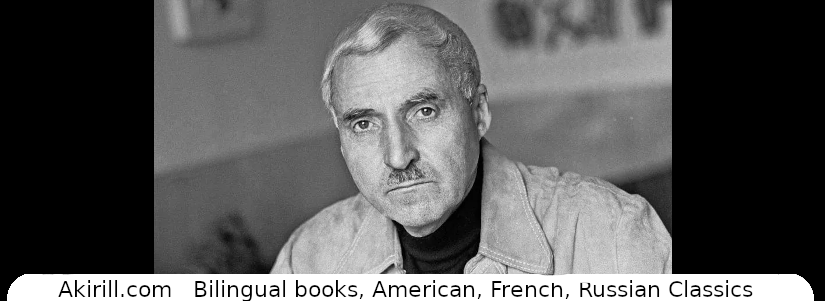

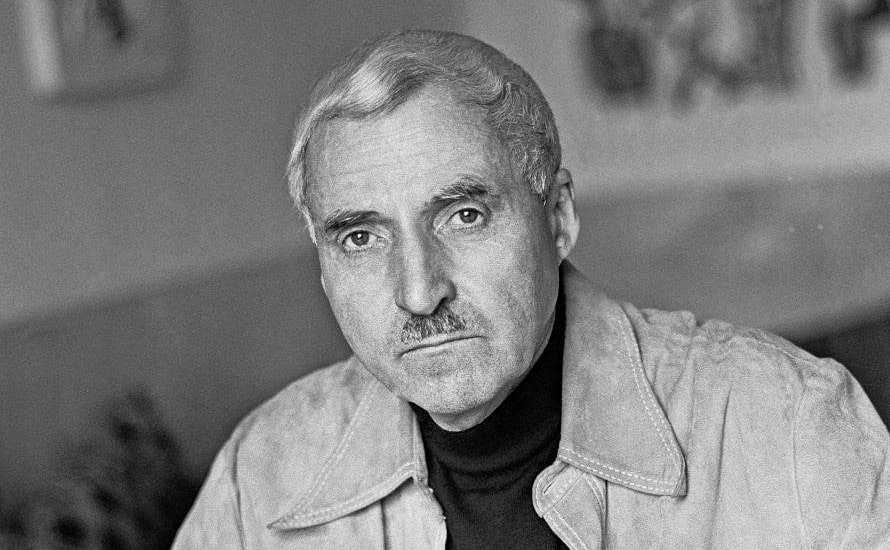

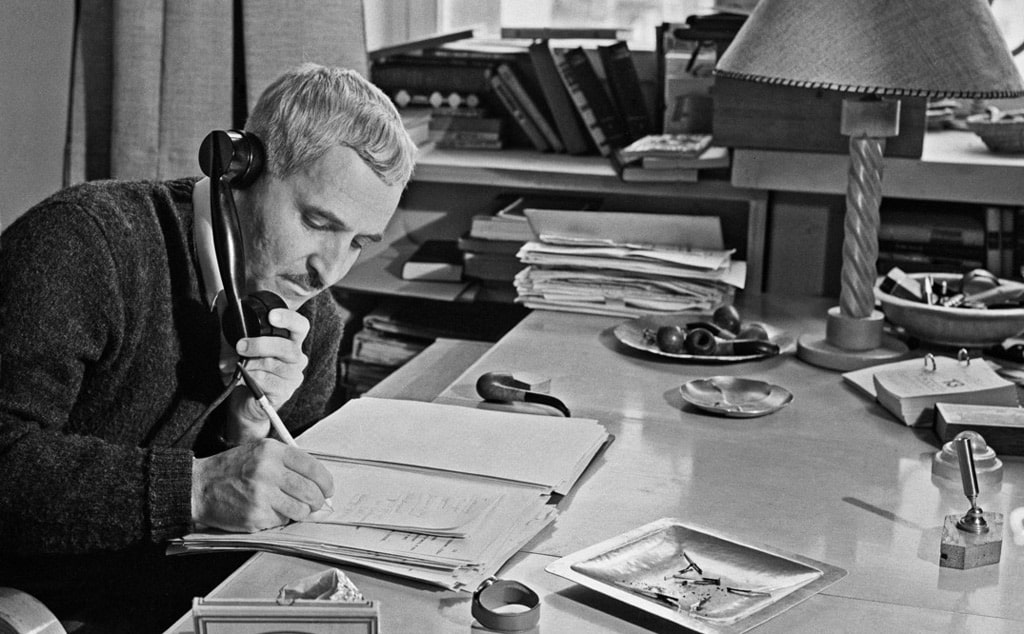

| Константин Симонов — Открытое письмо | Constantin Simonov – Lettre ouverte |

| |

Я вас обязан известить,

Что не дошло до адресата

Письмо, что в ящик опустить

Не постыдились вы когда-то. | Je suis obligé de vous informer,

Que la lettre déposée un jour sans honte dans la boîte aux lettres

n’est pas parvenue au destinataire. |

| |

Ваш муж не получил письма,

Он не был ранен словом пошлым,

Не вздрогнул, не сошел с ума,

Не проклял все, что было в прошлом. | Votre mari n’a pas reçu de lettre,

Il n’a pas été blessé par un mot vulgaire, Il n’a pas bronché, n’est pas devenu fou,

Il n’a pas maudit tout ce qui s’est passé dans le passé. |

| |

Когда он поднимал бойцов

В атаку у руин вокзала,

Тупая грубость ваших слов

Его, по счастью, не терзала. | Quand il a soulevé les combattants

Pendant l’attaque dans les ruines de la gare,

L’impolitesse contondante de vos paroles

ne l’a heureusement pas tourmenté. |

| |

Когда шагал он тяжело,

Стянув кровавой тряпкой рану,

Письмо от вас еще все шло,

Еще, по счастью, было рано. | Quand il marchait lourdement,

Tirant la plaie avec un chiffon ensanglanté,

Votre lettre arrivait encore,

Heureusement, il était encore tôt. |

| |

Когда на камни он упал

И смерть оборвала дыханье,

Он все еще не получал,

По счастью, вашего посланья. | Quand il est tombé sur les pierres

Et que la mort lui a coupé le souffle,

Il n’a heureusement pas encore reçu, votre message. |

| |

Могу вам сообщить о том,

Что, завернувши в плащ-палатки,

Мы ночью в сквере городском

Его зарыли после схватки. | Je peux vous dire que,

enveloppé dans des imperméables,

Nous l’avons enterré la nuit sur la place de la ville après le combat. |

| |

Стоит звезда из жести там

И рядом тополь — для приметы…

А впрочем, я забыл, что вам,

Наверно, безразлично это. | Il y a une étoile en étain là -bas

Et à côté se trouve un peuplier – pour un repére …

Mais, au fait, j’ai oublié que vous,

Probablement, ne vous en souciez pas. |

| |

Письмо нам утром принесли…

Его, за смертью адресата,

Между собой мы вслух прочли —

Уж вы простите нам, солдатам. | La lettre nous a été apportée le matin…

Après la mort du destinataire,

Nous l’avons lue à haute voix entre nous – Pardonnez-nous, soldats. |

| |

Быть может, память коротка

У вас. По общему желанью,

От имени всего полка

Я вам напомню содержанье. | Peut -être que votre mémoire est courte. Par volonté commune,

Au nom de tout le régiment,

je vous rappellerai le contenu. |

| |

Вы написали, что уж год,

Как вы знакомы с новым мужем.

А старый, если и придет,

Вам будет все равно ненужен. | Vous avez écrit que cela fait un an,

depuis que vous connaissez votre nouveau mari.

Et l’ancien, s’il vient,

vous sera complètement inutile. |

| |

Что вы не знаете беды,

Живете хорошо. И кстати,

Теперь вам никакой нужды

Нет в лейтенантском аттестате. | Que vous ne connaissez pas d’ennuis,

Vivez bien. Et au fait,

vous n’avez plus besoin d’

un certificat de lieutenant maintenant. |

| |

Чтоб писем он от вас не ждал

И вас не утруждал бы снова…

Вот именно: «не утруждал»…

Вы побольней искали слова. | Aussi qu’il n’attende pas de lettres de votre part

Et qu’il ne vous dérange plus …

C’est vrai: “il n’a pas pris la peine” …

Vous cherchiez des mots plus douloureux. |

| |

И все. И больше ничего.

Мы перечли их терпеливо,

Все те слова, что для него

В разлуки час в душе нашли вы. | Et c’est tout. Et rien de plus.

Nous les avons comptés patiemment,

Tous ces mots que pour lui

A l’heure de la séparation vous avez trouvés dans votre âme. |

| |

«Не утруждай». «Муж». «Аттестат»…

Да где ж вы душу потеряли?

Ведь он же был солдат, солдат!

Ведь мы за вас с ним умирали. | “Ne t’ embêtes pas.” “Mari”. “Certificat” …

Mais où avez-vous perdu votre âme?

Après tout, c’était un soldat, un soldat !

Après tout, nous battions avec lui pour vous. |

| |

Я не хочу судьею быть,

Не все разлуку побеждают,

Не все способны век любить,—

К несчастью, в жизни все бывает. | Je ne veux pas être juge,

Tout le monde ne surmonte pas la séparation,

Tout le monde n’est pas capable d’aimer pour toujours, –

Malheureusement, tout arrive dans la vie. |

| |

Но как могли вы, не пойму,

Стать, не страшась, причиной смерти,

Так равнодушно вдруг чуму

На фронт отправить нам в конверте? | Mais comment avez-vous pu, je ne comprends pas,

Devenir, sans crainte, la cause de la mort,

Si indifféremment nous envoyer tout d’un coup une peste au front dans une enveloppe ? |

| |

Ну хорошо, пусть не любим,

Пускай он больше вам ненужен,

Пусть жить вы будете с другим,

Бог с ним, там с мужем ли, не с мужем. | Eh bien même s’il n’est pas aimé,

Qu’il ne soit plus nécessaire pour vous,

Que vous viviez avec un autre,

Dieu le bénisse, que ce soit avec votre mari, pas avec votre mari. |

| |

Но ведь солдат не виноват

В том, что он отпуска не знает,

Что третий год себя подряд,

Вас защищая, утруждает. | Mais après tout, le soldat n’est pas à blâmer

Pour le fait qu’il ne connaît pas les vacances,

Que pour la troisième année consécutive,

vous protéger, dérange. |

| |

Что ж, написать вы не смогли

Пусть горьких слов, но благородных.

В своей душе их не нашли —

Так заняли бы где угодно. | Eh bien, vous ne pouviez pas écrire

Laissez des mots amers, mais des mots nobles.

Ils n’ont pas été trouvés dans votre âme

Vous pouviez les trouver n’importe où. |

| |

В отчизне нашей, к счастью, есть

Немало женских душ высоких,

Они б вам оказали честь —

Вам написали б эти строки; | Dans notre patrie, heureusement, il y a

beaucoup de hautes âmes féminines,

elles vous feraient honneur –

elles vous écriraient ces lignes; |

| |

Они б за вас слова нашли,

Чтоб облегчить тоску чужую.

От нас поклон им до земли,

Поклон за душу их большую. | Elles auraient trouvé des mots pour vous,

Pour soulager la tristesse d’un autre.

Pour nous, prosternez-vous devant elles jusqu’au sol, prosternez-vous

pour leur grande âme. |

| |

Не вам, а женщинам другим,

От нас отторженным войною,

О вас мы написать хотим,

Пусть знают — вы тому виною, | Pas à vous, mais à d’autres femmes,

arrachées à nous par la guerre,

Nous voulons écrire sur vous,

Qu’elles sachent que vous êtes coupable, |

| |

Что их мужья на фронте, тут,

Подчас в душе борясь с собою,

С невольною тревогой ждут

Из дома писем перед боем. | Que leurs maris sont au front, ici,

Parfois se battant avec eux-mêmes dans leur âme,

Avec une anxiété involontaire, ils attendent des lettres

de chez eux avant la bataille. |

| |

Мы ваше не к добру прочли,

Теперь нас втайне горечь мучит:

А вдруг не вы одна смогли,

Вдруг кто-нибудь еще получит? | Nous n’avons pas lu la vôtre avec plaisir,

Maintenant nous sommes secrètement tourmentés par l’amertume :

Et si vous n’étiez pas la seule à pouvoir, Et si quelqu’un d’autre en recevait une ? |

| |

На суд далеких жен своих

Мы вас пошлем. Вы клеветали

На них. Вы усомниться в них

Нам на минуту повод дали. | Au jugement de nos épouses lointaines

Nous vous enverrons.

Vous les avez calomnié.

Vous nous avez donné une raison

de douter d’elles pendant une minute. |

| |

Пускай поставят вам в вину,

Что душу птичью вы скрывали,

Что вы за женщину, жену,

Себя так долго выдавали. | Qu’elles vous reprochent, D’avoir

caché l’âme d’un oiseau , Quel genre

de femme, d’épouse, Vous vous êtes

livrée pendant si longtemps. |

| |

А бывший муж ваш — он убит.

Все хорошо. Живите с новым.

Уж мертвый вас не оскорбит

В письме давно ненужным словом. | Et votre ex-mari est mort.

Tout va bien. Vivez avec le nouveau.

Déjà les morts ne vous offenseront pas

Dans une lettre pendant longtemps un mot inutile. |

| |

Живите, не боясь вины,

Он не напишет, не ответит

И, в город возвратись с войны,

С другим вас под руку не встретит. | Vivez sans crainte de culpabilité,

Il n’écrira pas, ne répondra pas

Et, de retour à la ville de la guerre,

Il ne vous rencontrera pas au bras d’un autre. |

| |

Лишь за одно еще простить

Придется вам его — за то, что,

Наверно, с месяц приносить

Еще вам будет письма почта. | Seulement une chose de plus à pardonner ,

vous devrez lui pardonner – pour le fait que, probablement pendant des mois, on vous apportera encore des lettres de la poste. |

| |

Уж ничего не сделать тут —

Письмо медлительнее пули.

К вам письма в сентябре придут,

А он убит еще в июле. | Il n’y a rien qui peut être fait ici –

Une lettre est plus lente qu’une balle.

Des lettres vous parviendront en septembre,

et il a été tué en juillet. |

| |

О вас там каждая строка,

Вам это, верно, неприятно —

Так я от имени полка

Беру его слова обратно. | Chaque ligne parle de vous,

c’est probablement désagréable pour vous –

Alors au nom du régiment

je retire ses propos. |

| |

Примите же в конце от нас

Презренье наше на прощанье.

Не уважающие вас

Покойного однополчане. | Acceptez à la fin de notre part,

notre mépris de la séparation.

Des camarades soldats

qui ne vous respectent pas . |

| |

По поручению офицеров полка

К. Симонов

___________________________

[Женщине из города Вичуга] | Au nom des officiers du régiment

K. Simonov

_____________________

[À une femme de la ville de Vichuga] |

| |