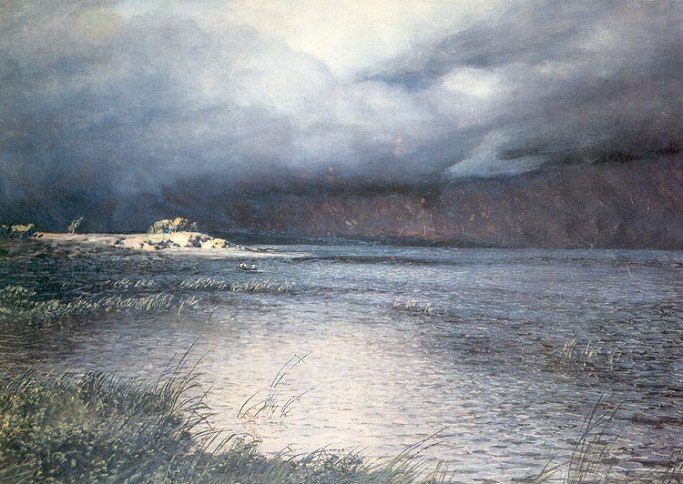

The painting “Quiet” (Притихло), which is referred as “landscapes of mood” is one of the most famous and most significant works of Nikolai Dubovskoy (Николай Дубовской). It is a landscape which is an oil on canvas of 76.5 X 128 cm completed in 1890 and now belonging to the State Russian Museum of Saint Petersburg. The painting was first exposed at the 18th exhibition of the Association of Traveling Art Exhibition with great success. Emperor Alexander III immediately purchased it, and Nikolai Dubovskoy had to make a copy for Pavel Tretyakov who also wanted to buy it. The copy of 86 X143 cm is in the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

When painting the painting “Quiet”, the artist used a sketch painted on the Baltic coast. In one of his letters, Nikolai Dubovskoy wrote: “The motive for creating this picture was that exciting feeling that took possession of me many times when observing nature at a moment of silence before a big thunderstorm or in the intervals between two thunderstorms, when it is difficult to breathe, when you feel your insignificance at the approach of the elements. This state in nature – the silence before a thunderstorm – can be expressed in one word, “Quiet”. This is the title of my painting.”

There are several more author’s repetitions of the painting. One from 1896, is in the Poltava Art Museum. Another one, dated 1913-1915, belongs to the Samara Regional Art Museum.

There is also an undated author’s repetition is in the Rostov Regional Museum of Fine Arts, as well as in The National Art Museum of Belarus. There is a repetition called “A cloud is approaching” from 1912 which is in the Novocherkassk Museum of the History of the Don Cossacks.

The collection Vladimir-Suzdal Historical, Artistic and Architectural Museum-Reserve also include a repetition of the oil on canvas of 69 × 112 cm from 1890s, and in the Vologda Regional Art Gallery there is a repetition of “Quiet. A cloud is coming”, dated 1912.

Another one from 1890, also an oil on canvas of 85.6 × 133 cm is in the collection of the Zimmerli Museum of Rutgers University situated in New Brunswic, New Jersey, USA.

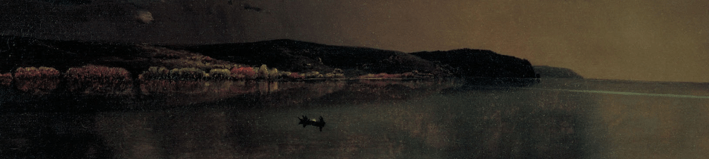

The painting depicts a seascape. Thunderclouds occupying almost the entire upper part, hang over the water. Their upper part illuminated by the sun, resembles white cotton wool, and the lower part is filled with ominous blackness.

There is no wind, and light and dark clouds are reflected in the smooth and blackened water.

In the distance you can see the dark strip of the coast, on which there are houses of some village. Bright orange-red crowns of trees and bushes, standing out against the background of a dark forest, emphasize the tension of the atmosphere.

If you look closely, on a smooth, almost glossy surface of the water, you can see a tiny boat that is moving towards the shore with a rower. But the land is still far away, which cannot but inspire fear in the owner of this boat. It seems that this small ship is so defenseless against an approaching thunderstorm that it is about to get lost somewhere in the sea waves.

The tense state of nature before the storm is clearly felt, looking at the menacing rain clouds, it seems that something terrible is about to happen. But the feeling of a person’s helplessness in front of the natural elements, expressed by Dubovsky in the painting “Quiet”, should not be taken as its main content. It cannot be assumed that the artist’s goal was the glorification of the elements and its power over people. This is evidenced by the fact that for the image he chose not the storm itself, but the moment preceding it. A small boat heading towards the shore and striving to reach it as quickly as possible does not at all emphasize the impotence of a person as we do not know whether the rower will reach the shore safely, however, as soon as we notice him, we cannot but wish that he reaches the shore safely.

I hope you enjoyed this painting as much as I did

| If you liked this article, subscribe , put likes, write comments! |

| Share on social networks |

| Check out Our Latest Posts |

- Poèmes et peinture, semaine du 25 janvier 2026

- Poems and painting, Week of January 25, 2026

- Poèmes et peinture, semaine du 18 janvier 2026

- Poems and painting, Week of January 18, 2026

- Poèmes et peinture, semaine du 11 janvier 2026

- Poems and painting, Week of January 11, 2026

© 2022 Akirill.com – All Rights Reserved